Designing Council Teams for the Real World: Why Whole‑Systems Thinking Matters

- truthaboutlocalgov

- Nov 26, 2025

- 8 min read

Local government isn’t a machine with neatly separated parts it’s a living system.

Every council is a complex organism, not a collection of isolated departments. Decisions made in one area whether it’s housing policy, school transport, or adult social care send ripples across the entire organisation and into the lives of residents. A funding shift in one service can trigger unintended consequences elsewhere: cut early help and you’ll see rising demand in child protection; reduce planning capacity and regeneration slows, affecting economic growth.

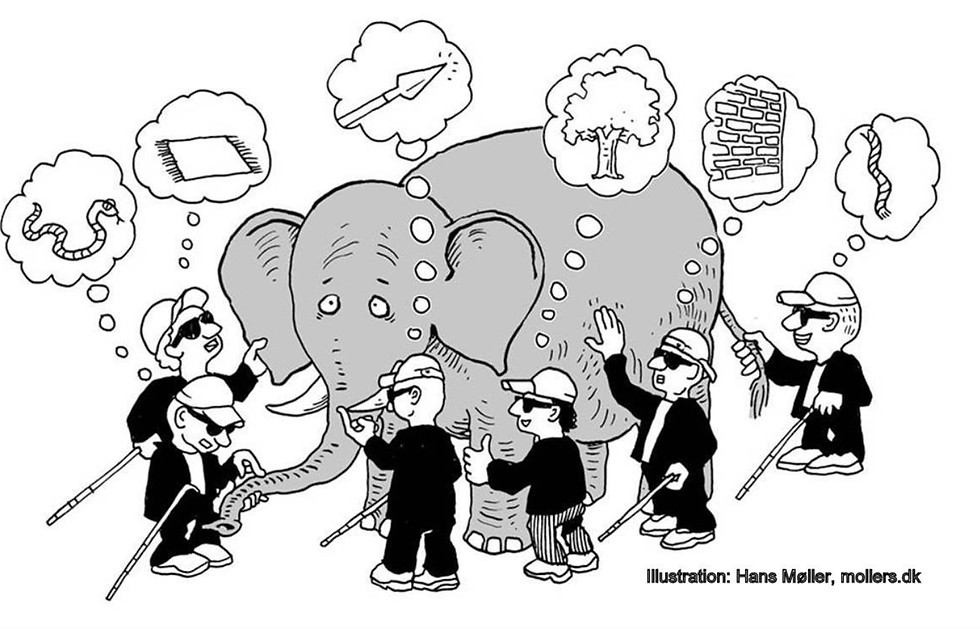

Yet, despite this interconnected reality, we often design teams as if they operate in sealed compartments. Structures are drawn like boxes on a chart, with neat reporting lines and rigid boundaries. The result? Siloed teams that struggle to collaborate, duplicate effort, and miss opportunities to solve problems holistically. When services don’t talk to each other, residents experience fragmented support and councils waste scarce resources.

Whole‑systems thinking offers a different lens. It invites us to see councils as networks of relationships and flows, not static hierarchies. It’s about recognising that the whole behaves differently from the sum of its parts and that success depends on the quality of the connections between those parts. In a true system, the magic happens in the spaces between teams: the conversations, the shared data, the joint decisions. That’s where innovation and resilience emerge.

Why This Matters Now

The financial context is stark. Real‑terms core funding for English councils rose just 4% between 2015/16 and 2023/24, yet funding per person fell by 1% as demand soared. Social care now consumes 58% of local authority spending, leaving prevention and discretionary services squeezed. Since 2020, 42 councils have needed exceptional financial support to stay afloat.

This isn’t a temporary squeeze it’s a structural challenge. Efficiency tweaks and incremental cuts won’t solve it. The issues councils face temporary accommodation, SEND pressures, health inequalities are systemic problems. They cross departmental boundaries and require joined‑up responses. Designing teams in isolation is like trying to fix a spider’s web by tugging one strand you distort the whole pattern. To thrive in this environment, councils need organisational designs that work across boundaries, foster collaboration, and enable adaptive learning. Whole‑systems thinking isn’t optional anymore; it’s the foundation for sustainability and better outcomes.

Six Questions to Shape Better Design

When councils redesign teams, the instinct is often to start with the visible mechanics: structure charts, reporting lines, and job descriptions. These are tangible and easy to draw on a whiteboard. But they only scratch the surface. They tell us who reports to whom, not how work actually flows, or how relationships shape outcomes.

If we want organisations that thrive in complexity where housing decisions connect to health outcomes, and education links to economic growth we need to start with systemic questions. These questions uncover the hidden architecture of councils: the relationships, cultural norms, and contextual forces that drive behaviour. The six questions below, inspired by Daniel Christian Wahl, are not abstract theory. They are practical tools for designing teams that deliver joined-up outcomes for communities, rather than fragmented services.

1. What system are we designing for and where do we draw the boundary?

Before we sketch any structure, we must define the system in scope. Are we designing for the council workforce alone? Or for the wider ecosystem that includes NHS partners, housing associations, voluntary groups, contractors, and even community networks?

Boundaries matter because they determine who shares accountability and who gets a voice in decision-making. Too often, councils draw boundaries too tightly, focusing only on internal teams. The result? Strategies that fail because they ignore the interdependencies that shape real-world outcomes.

Why it matters:

If your homelessness strategy excludes health partners, you’ll miss the link between housing insecurity and mental health.

If your SEND transport redesign ignores Highways and Finance, you’ll create bottlenecks and overspends.

Real-world example:The UK Government’s Systems-Wide Evaluation of Homelessness found that fragmented funding streams and siloed governance were major barriers to prevention. Councils that widened boundaries to include health, housing, and voluntary partners achieved better outcomes and reduced crisis spending.

Design principle: Treat boundaries as interfaces for collaboration, not walls. Think of them as porous membranes where ideas, data, and resources flow freely. Councils that embrace this mindset move from “us and them” to shared stewardship a culture where success is measured by collective impact, not departmental wins.

2. Which actors and relationships drive behaviour?

Councils are powered by relationships, not just processes. It’s not enough to know who sits where; we need to understand who influences outcomes and how. Mapping these relationships reveals the “critical handshakes” that make or break success: Housing ↔ Children’s Services, Planning ↔ Public Health, Finance ↔ Adult Social Care.

Why it matters:

A SEND transport issue isn’t just Education it involves Finance, Highways, and sometimes Health.

Delays in hospital discharge often stem from weak links between Adult Social Care and NHS discharge teams.

Real-world example: In Sefton, integrated discharge planning through the ICS reduced hospital delays and improved patient outcomes by embedding council social workers in NHS teams. Similarly, Warwickshire’s frailty service kept half of patients at home after falls by using integrated neighbourhood teams.

Action: Use tools like relationship mapping or social network analysis to identify where collaboration is strong and where it’s brittle. Then design roles and governance to strengthen those weak points.

3. What wider context shapes the system?

No team operates in isolation. Funding volatility, demographic shifts, political priorities, and regulatory changes all shape behaviour. Designing for stability in a world of uncertainty is a recipe for failure.

Why it matters:

Real-terms funding for councils has grown just 4% since 2015, while demand for social care and SEND has exploded.

Social care now consumes 58% of local authority spending, leaving prevention squeezed.

Since 2020, 42 councils have needed exceptional financial support to stay afloat.

Design principle: Build adaptability into structures. Flexible roles, pooled resources, and governance that can pivot when policy or demand changes are essential. Think modular teams that can scale up or down without breaking.

4. How do our values shape what we see?

Our worldview frames our decisions. If we see teams as “cost centres,” we design for cuts and compliance. If we see them as “value creators for place,” we design for prevention, innovation, and learning.

Why it matters:

Language drives behaviour. Calling a service “statutory minimum” signals survival mode; calling it “community wellbeing” invites creativity and partnership.

Councils that adopt a place-based value lens tend to invest in prevention and cross-sector collaboration, reducing long-term costs.

Quote to use:

“In a learning organization, leaders are designers, stewards, and teachers. They are responsible for building organizations where people continually expand their capabilities to understand complexity.” Peter Senge

Action: Audit the language in your strategies and governance documents. Does it reinforce scarcity and control or stewardship and shared purpose?

5. What outcomes emerge only from the whole?

Some results can’t be achieved by any single silo they emerge from collaboration. Integrated discharge planning, joint Housing–Public Health casework, or multi-agency early help hubs are classic examples.

Why it matters:

Emergent properties are the hidden power of systems. When teams work together, they create solutions no one department could deliver alone.

Councils that design for emergence by aligning goals and sharing accountability see better outcomes for residents and better use of resources.

Real-world example: Public Health England’s whole-systems approach to obesity showed measurable improvements in health behaviours when councils engaged partners and aligned governance.

Action: Identify 3–5 priority outcomes that require cross-team effort. Then design governance and metrics around those outcomes, not just departmental KPIs.

6. How does our participation influence the system?

We’re not neutral observers we shape the system by how we act and speak. When leaders talk about “working together differently,” behaviours shift. Governance routines, shared dashboards, and joint performance measures reinforce that shift.

Why it matters:

Culture eats structure for breakfast. You can design the perfect org chart, but if leaders cling to siloed thinking, nothing changes.

Councils that make collaboration visible through joint boards, shared data, and public recognition embed systemic behaviours faster.

Action: Celebrate cross-team wins. Build rituals that reinforce collaboration, like joint learning sessions or integrated performance reviews.

The Big Picture

These six questions aren’t a checklist they’re a mindset. They help us move beyond structure charts and think about relationships, context, and culture. Councils that ask them design organisations that are adaptive, resilient, and focused on outcomes that matter for communities.

Evidence That It Works

Whole-systems thinking isn’t just a theory it’s delivering results in UK local government where councils embrace collaboration and shared accountability.

Integrated care partnerships are reducing hospital delays and improving community outcomes.

Councils working with NHS partners through Integrated Care Systems (ICS) have transformed discharge planning. For example, Warwickshire’s frailty service kept half of patients at home after falls by embedding social care professionals in NHS teams. Similarly, Sefton Council reduced delayed transfers of care by co-designing discharge pathways with health partners. These changes didn’t come from tweaking a single department they emerged from systemic redesign.

Whole-systems approaches to obesity show measurable improvements in health behaviours.

Public Health England’s guidance on whole-systems approaches to obesity has been adopted by councils like Leeds and Birmingham. By engaging schools, leisure providers, housing teams, and community organisations, these councils created environments that support healthier choices. The result? Increased physical activity and improved diet behaviours across communities.

“Working together differently is the secret sauce for better health and care outcomes.” NHS Confederation

Design Principles for Councils

If you want systemic outcomes, you need systemic design. Here are four principles that turn theory into practice:

1. Design for interfaces, not just boxes.

Structure charts show boxes, but outcomes happen in the spaces between them. Re-engineer handovers and shared workflows for example, between Housing and Adult Social Care for homelessness prevention. Councils that focus on interfaces reduce duplication and improve resident experience.

2. Make learning a habit.

Volatility is the new normal. Councils that embed reflection and adaptation through peer reviews, learning loops, and cross-team retrospectives outperform those that cling to rigid plans. The Local Government Association’s peer challenge programme is a proven model for systemic learning.

3. Govern for prevention.

Short-term fixes cost more later. Shift resources upstream to tackle root causes whether that’s early help for families or proactive housing interventions. The NAO warns that councils underinvest in prevention because governance focuses on statutory minimums rather than long-term value.

4. Use facilitative leadership.

When success depends on cross-agency behaviour, command-and-control fails. Leaders must act as stewards and convenors, creating conditions for collaboration rather than issuing directives. Councils that adopt facilitative leadership see stronger partnerships and more resilient systems.

“Leaders are designers, stewards, and teachers. They are responsible for building organisations where people continually expand their capabilities to understand complexity.” Peter Senge

Conclusion: The Bottom Line

Whole-systems thinking isn’t a buzzword. It’s a practical response to the complexity councils face every day. When we design teams with these principles, we create organisations that are adaptive, collaborative, and focused on outcomes that matter for communities. But here’s the bigger question: as local government moves through reorganisation and devolution, are we truly optimising this opportunity for whole-system design? Or are we simply rearranging the boxes on our own org charts while leaving the deeper patterns of fragmentation untouched?

Because the stakes are high. The challenges we face health inequalities, housing crises, SEND pressures are systemic. They cross boundaries between councils, NHS bodies, housing associations, and voluntary organisations. If we fail to design for collaboration across this entire ecosystem, we risk repeating the same mistakes under a new structure. So ask yourself:

Are we thinking boldly enough? Are we using this moment to create integrated systems that deliver better outcomes for residents or just shifting responsibilities without changing the way we work?

If we get this right, we won’t just survive the next wave of change. We’ll build councils that are resilient, innovative, and capable of shaping healthier, fairer, and more sustainable communities. That’s the promise of whole systems thinking and it’s ours to seize.