Why Governance, Not Reorganisation, Will Shape the Next Decade of Local Government

- truthaboutlocalgov

- Dec 9, 2025

- 8 min read

Bigger councils, same problems – unless governance catches up

The latest wave of council reform is moving across England. County deals, new combined authorities and proposals for structural reorganisation have created renewed debate about what local government should look like. There is a wider conversation about democratic deficits happening, in places you wouldn’t think. The general public disenfranchisement with politics currently raises a serious question about legitimacy and mandate, if election turnout is low. But those are minor niggles that can be quickly rectified, the more important but overlooked questions that everyone should be asking:

What kind of governance will take better decisions?

Which option will unlock funding and deliver outcomes at speed?

From structures to systems – and money

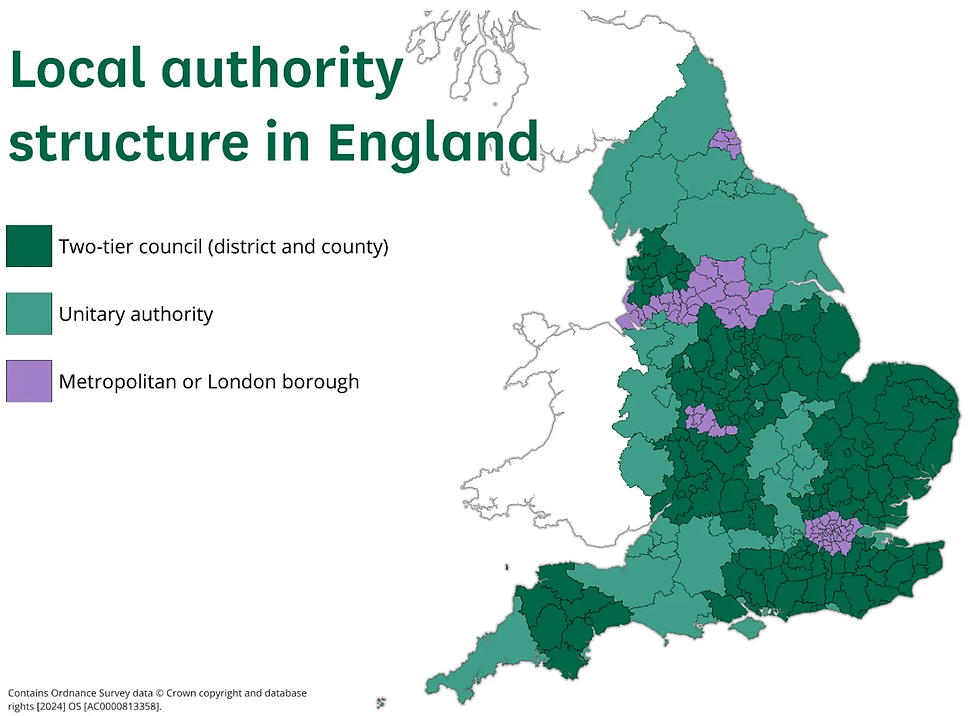

England currently operates a patchwork of governance models that can be as confusing for councillors as for residents. As our towns and cities have expanded and become more connected, not only physically, but also through where and how people live, work and spend leisure, our councils and related policies have also expanded.

In two-tier areas, districts handle planning and housing while counties deliver strategic services such as education, transport and social care. This supports strong local identities, mostly to the disadvantage of joined-up planning or service delivery, but creates friction when major infrastructure or housing decisions must be coordinated across several districts.

Unitary authorities simplify this landscape. Recent reorganisations in Dorset, North Yorkshire, Cumbria and Somerset demonstrate the appeal a single point of accountability and integrated services have. But unitary status alone does not fix the gaps around transport, spatial planning, and the ability to assemble land and fund infrastructure at scale.

This is where devolution and funding powers matter as much as lines on the map. Combined authorities and metro mayors have not just gained new responsibilities, they have secured access to serious long-term investment, if they work for it.

Strong devolution has resulted in billions of funding up and down the country

Greater Manchester has negotiated a trailblazer devolution deal that moves towards a single, department-style funding settlement and long-term retention of business rates. This consolidates a range of grants into one pot and strengthens local fiscal autonomy.

Through its investment funds, Greater Manchester has deployed around £1.2 billion into commercial property, housing and business growth, with its Housing Investment Loan Fund alone on track to support around 10,000 homes and thousands of jobs.

The West Midlands Combined Authority trailblazer deal includes a landmark housing package worth up to £500 million for brownfield regeneration and affordable housing, alongside a decade-long business rates retention agreement worth around £45 million a year, and a new single funding pot.

The Liverpool City Region’s first devolution agreement secured £900 million over 30 years, creating a Strategic Investment Fund that blends devolved public money with private investment to back transport, skills, innovation and housing.

These are not abstract arrangements; without devolution this funding would not have been unlocked as easily, cleanly or in such volume. They are clear evidence of what can happen in the new order. They underpin long-term partnerships with business, pension funds and investors.

Greater Manchester’s new £1 billion “Good Growth” fund was co-designed with its Local Government Pension Scheme and is explicitly framed as a vehicle to “unlock massive private sector investment”, using public capital as the first-loss or pump-priming layer. Larger authorities have the clout to be real partners for investment.

In the emerging national model mayors are also being placed at the heart of the new National Wealth Fund and Office for Investment agenda, with government committing to work directly with regional leaders in places such as Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, the West Midlands, the Liverpool City Region and the North East to crowd in private capital. That combination of strategic powers plus genuine investment leverage is what makes governance design more than a tidying-up exercise.

London: the outlier with extraordinary powers

At the other end of the spectrum sits London, where the governance question is now becoming more acute. The Mayor of London heads the Greater London Authority and prepares the London Plan, the statutory spatial development strategy that shapes where and how London grows over the next 20–25 years.

To implement that strategy, the Mayor holds an unusually concentrated bundle of planning and land powers:

For certain “referable” applications (larger schemes or those of strategic importance) the Mayor can direct a borough to refuse permission if the proposal conflicts with the London Plan, or “call in” the application and become the local planning authority, taking the final decision at a public hearing.

Through Mayoral Development Corporations such as the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation, the Mayor can create bodies with combined powers over planning, land assembly, housing and infrastructure delivery, including compulsory purchase.

City Hall can deploy capital to acquire land directly or via partners to support regeneration and housing objectives, with central government funding explicitly channelled to the GLA family.

On top of this, national planning reforms now in train will strengthen compulsory purchase powers for councils and mayors, including removing “hope value” from compensation in defined circumstances and removing the need for central government sign-off on many Compulsory Purchase Orders.

Overlay those national changes with the London Plan review process now under way and the picture becomes clearer. The Mayor is simultaneously:

proposing the next strategic planning framework for the capital,

holding the power to call in and decide many large applications,

controlling or influencing significant landholdings and regeneration vehicles, and

operating within a national regime that is explicitly shifting more land assembly power to local and mayoral bodies.

Individually each of these powers is rooted in statute and subject to checks, including Secretary of State oversight. Taken together, they amount to a uniquely centralised planning role for one directly elected individual in the English system.

London’s leaders push back: a new devolution settlement?

It is precisely because of this concentration that London borough leaders are now seeking a very different governance balance. In April 2025, the leaders of all 32 boroughs issued a joint cross-party statement calling for a new devolution settlement for the capital, centred on formal joint decision-making between the Mayor and boroughs over relevant powers and funding, including any future integrated financial settlement.

The organisation London Councils has proposed a “Combined Board” made up of the Mayor and the cross-party executive of London councils, arguing that:

the current model relies on voluntary collaboration and case-by-case negotiation,

there is no formal borough role in GLA executive decisions, unlike the cabinet-plus-mayor model in combined authorities such as Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, and

without change, London risks being the only part of England where council leaders have no formal say over their strategic authority.

In other words, London already has the “strong mayor” model (strategic planning, transport and policing concentrated in City Hall) but without the structured, statutory place for local leaders that underpins the combined authority model elsewhere. For counties like Surrey, looking at whether and how to create a strategic tier above unitaries, this London debate is highly relevant. It shows both the power and the political risks of designing a system where the mayor has deep, integrated powers, but council leaders are formally at arm’s length. Two points stand out:

Scale and duration give mayors confidence: 30-year “earn back” or gainshare arrangements give mayors the confidence to assemble land, co-fund infrastructure and sequence investment in a way that simple grant bidding never could.

Joint ventures between public and private can unlock huge potential: business boards, pension funds and regional investment vehicles are not afterthoughts; they sit inside the governance architecture and shape decisions alongside local leaders.

For any area contemplating reorganisation or a new strategic tier, the question is therefore not just “unitary or two-tier”, but whether the governance model is credible enough to negotiate similar long-term funding and partnerships.

As Leader of Surrey County Council, Tim Oliver said to this series recently:

“…there is absolutely no, from a governance perspective and a delivery perspective, no advantage to reorganising without a mayor, because you’re just going to end up spending a lot of time and money disaggregating…”

Democracy, communication and consent

There is another piece of this story that is easy to overlook. That is the public understanding and resulting democratic legitimacy of any new body. Even before the current wave of changes were announced, many residents struggled to understand what their local council does. This is further compounded in tier two areas with split lines of responsibility. Layering new structures, including unitaries, combined authorities, mayors, and development corporations on top of this confusion should in theory bring clarity: fewer bodies, clearer lines of responsibility, and more visible leadership.

In practice, without proactive and plain-speaking communication campaigns, it risks doing the opposite.

Turnout figures underline the challenge facing politicians at the next election. The 2024 local elections in the UK recorded turnout of around 30%, far below general election levels and markedly lower than typical participation in the 1980s and early 1990s, when English local election turnout often sat between 40% and 50%. Case-study work on English cities shows ward-level by-elections where turnout has dipped into the low 20s.

That combination matters. In a ward where only three in ten electors vote, and the winning candidate takes, say, 40% of those votes in a competitive field, you are effectively electing local representatives on the active support of little more than one in eight or one in seven eligible voters. In some by-elections with very low turnout, the figure is closer to one in five.

Former Elmbridge councillor, Andrew Kelly was reflecting on the reduction in councillor numbers and the resulting casework increase, and put it starkly:

“From a democratic point of view, which is where I more sit, it does lead to people’s voices, I think, being less listened to.”

Describing repeated cycles of structural reform and merger, he added:

“All we do each time is create all these sorts of complications… and I think it does lessen democracy.”

From the author’s perspective, that raises a serious thought: what does democratic legitimacy look like in a more powerful, more centralised local system of government, if only a minority understand the system or take part in choosing its leaders?

As a friend returning from Australia put it to me, in that country politicians try to outdo each other on how many new homes they promise they will build, unlike here where the opposite case is more the norm; the reason, compulsory voting means young people are required to turn out and the conversation becomes truly national and intergenerational.

If changes proceed without a corresponding investment in public explanation (who does what, who to hold to account, how decisions are made) then even the most elegant governance diagrams will be experienced by residents as a further layer of distant complexity. That is especially true if the new bodies hold major powers over land, housing and transport, where decisions are visible and often contentious.

What this means for the next phase of LGR

For counties like Surrey and other areas now entering the reorganisation and devolution conversation, three tests follow.

1. Strategic clarity

There needs to be a clearly identifiable body (ideally led by a directly elected figure) with the powers and funding to integrate transport, planning, housing and economic strategy at the scale the real economy operates. Without this you are repeating the problems inherent with the last.

2. Embedded local voice

Council leaders must have a formal, not just informal, place in strategic decision-making, to ensure that local democratic mandates have a route into regional choices. The London borough leaders’ call for a Combined Board model is one expression of this.

3. Democratic and communication strategy

Change must be accompanied by a serious plan to explain changes to the public in plain language, show who is accountable for which decisions, and make it easier to participate, otherwise low and uneven turnout will continue to hollow out legitimacy, just as new powers are being centralised.

Reorganisation is visible and tempting: it produces maps, diagrams and press releases. The harder work is governance, who sits in the room, who controls the purse strings, who can assemble land and who the public sees as responsible when things go wrong.

England now has decades of experience, from Greater Manchester’s collaborative cabinet to London’s powerful mayoralty and the funding deals in West Midlands and Liverpool City Region. The next generation of reforms will be judged not by how tidy the organisational chart looks, but by whether they can unlock investment, deliver decisions at pace and sustain democratic consent in an era of low participation and high expectations.

Author: Rowan Cole

Founder & Director at COALFACE TM