Applying Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions in UK Local Government: A Framework for Cultural Insight

- truthaboutlocalgov

- Nov 16, 2025

- 8 min read

“Culture is the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group from another.” – Geert Hofstede

This statement captures the essence of why culture matters in any organisation, and it is particularly relevant for local government. Councils are not just administrative bodies; they are complex organisations with deeply ingrained values, behaviours, and norms that influence how decisions are made and services are delivered. Culture shapes everything from how staff interact with elected members to how partnerships with health, police, and voluntary sectors are managed. Local government in the UK faces unique pressures:

Financial constraints and the need to deliver more with less.

Policy volatility, driven by national political cycles.

Community diversity, requiring sensitivity to cultural differences within the population.

Collaborative governance, where success depends on working effectively with multiple agencies and stakeholders.

In this environment, understanding organisational culture is not a “nice to have” it is a strategic necessity. A council’s culture can accelerate transformation or derail it. For example, a culture that values openness and innovation will embrace digital transformation, while one that prioritises risk avoidance may resist change even when budgets demand it.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions model offers a structured lens to assess these tendencies. By examining dimensions such as Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance, leaders can anticipate where friction might occur whether between departments, in joint ventures, or when introducing new ways of working. It moves culture from being an abstract concept to something measurable and actionable. For local government leaders, this means:

Diagnosing cultural traits before major change programmes to avoid resistance.

Aligning leadership behaviours with cultural realities, rather than imposing models that clash with ingrained norms.

Building cultural competence in partnerships, especially where councils work with organisations from different sectors or countries.

In short, Hofstede’s framework helps councils see beyond structures and processes to the underlying “programming” that drives behaviour. And in a sector where collaboration and trust are paramount, that insight can make the difference between success and failure.

Why Hofstede Matters for Councils

Local authorities are not just administrative entities they are cultural ecosystems with thousands of employees, elected members, and partner organisations working together to deliver essential services. With annual budgets exceeding £100 billion, councils oversee critical areas such as education, housing, social care, and environmental services. These responsibilities demand not only operational efficiency but also cultural alignment across diverse teams and external stakeholders. Culture becomes a strategic lever in this context. When councils embark on transformation programmes whether digitalisation, shared services, or structural mergers the success or failure often hinges on cultural compatibility. Research into council mergers, such as Cornwall’s transition to a unitary authority, highlights that cultural misalignment can derail progress even when the structural and financial case for change is strong. Staff resistance, conflicting values, and leadership disconnects are common symptoms of cultural friction.

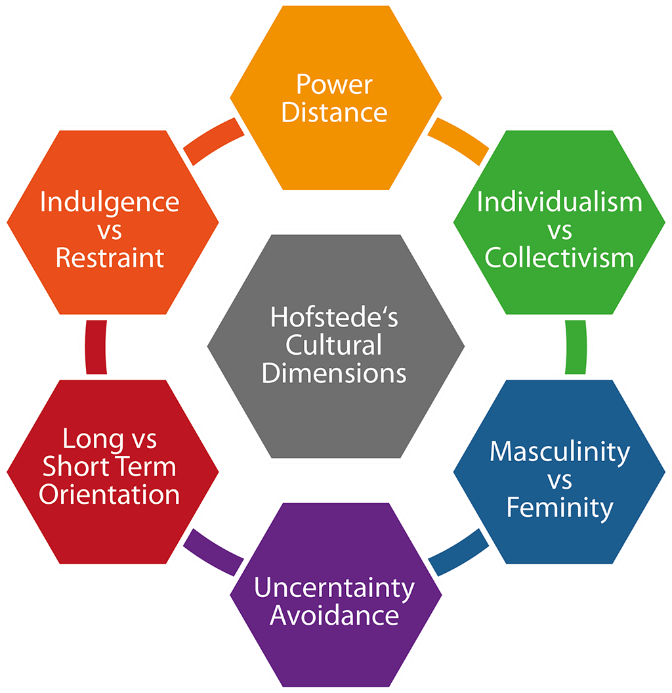

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions model provides a structured, evidence-based lens to diagnose these dynamics. By examining six key dimensions Power Distance, Individualism vs. Collectivism, Uncertainty Avoidance, Masculinity vs. Femininity, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence leaders can anticipate where tensions may arise and design interventions that respect underlying cultural norms.

UK Scores and Local Government Implications

According to Hofstede Insights, the UK ranks:

Power Distance: 35

Individualism: 89

Uncertainty Avoidance: 35

Masculinity: 66

Long-Term Orientation: 51

Indulgence: 69

These scores reveal a national culture that values low hierarchy, high individual autonomy, and moderate flexibility, with a tendency towards competitive achievement and enjoyment of life. For councils, this translates into several practical implications:

Low Power Distance (35): Staff expect participative decision-making and transparency. Imposing rigid hierarchies or top-down directives can trigger resistance, especially during organisational change.

High Individualism (89): Employees value autonomy and personal accountability, which supports innovation but can hinder cross-departmental collaboration unless actively managed.

Low Uncertainty Avoidance (35): Councils are culturally comfortable with ambiguity, which aids adaptive policymaking but can lead to inconsistent practices without clear frameworks.

Masculinity (66): A results-driven orientation aligns with performance targets but may clash with public service values of empathy and care, particularly in social services.

Moderate Long-Term Orientation (51): Councils balance strategic planning with short-term political cycles, making cultural continuity challenging during leadership changes.

High Indulgence (69): Wellbeing initiatives and flexible working resonate strongly with staff expectations, influencing HR policy and retention strategies.

1. Power Distance (35)

The UK’s low Power Distance score reflects a cultural preference for equality and participative decision-making. In councils, this manifests as relatively flat organisational structures, open-door policies, and informal communication styles. Staff often expect to have a voice in shaping policies and processes, which aligns with democratic governance principles.

However, this cultural trait can create challenges when councils collaborate with organisations from high Power Distance cultures such as overseas contractors or even certain UK public bodies with more hierarchical traditions. For example, when implementing shared services with the NHS or police, differences in authority boundaries can lead to confusion or frustration.

Practical Implication: Councils should establish clear governance frameworks and communication protocols in joint ventures to prevent misunderstandings. Leadership training should also include cultural awareness to prepare managers for these dynamics.

2. Individualism vs. Collectivism (89)

UK councils operate in a highly individualistic culture, where autonomy and personal accountability are prized. This supports innovation and empowers staff to take ownership of projects. However, it can also hinder collaboration across departments, particularly in large transformation programmes that require collective effort.

Leadership programmes often struggle to embed collectivist behaviours in such contexts, as noted in UK leadership training research. Councils may find that siloed working persists despite structural changes, slowing down progress on shared objectives like climate action or integrated care.

Practical Tip: Incentivise team-based outcomes and recognise collaborative achievements in performance reviews. Embedding cross-functional project teams and shared KPIs can help counterbalance individualistic tendencies.

3. Uncertainty Avoidance (35)

The UK’s low score indicates a cultural tolerance for ambiguity, which can be advantageous for adaptive policymaking and innovation. Councils are often willing to experiment with new service delivery models or pilot schemes without exhaustive rulebooks.

However, during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic this flexibility can lead to inconsistent practices across departments or regions. While some councils embraced rapid digital transformation, others lagged due to unclear protocols.

Policy Angle: Councils should standardise critical protocols for emergencies while maintaining room for local discretion in less time-sensitive areas. This balance ensures resilience without stifling innovation.

4. Masculinity vs. Femininity (66)

The UK leans towards a masculine orientation, valuing competitiveness and achievement. In local government, this is reflected in performance-driven cultures and a focus on measurable outcomes, such as meeting housing targets or reducing waiting times.

Yet, public service ethos demands empathy, collaboration, and community engagement traits associated with a more feminine orientation. Studies of council mergers show tension between results-oriented managers and staff prioritising social values and wellbeing.

Practical Insight: Leadership development should emphasise emotional intelligence and stakeholder engagement alongside performance metrics to balance these competing priorities.

5. Long-Term Orientation (51)

A moderate score suggests councils balance strategic planning with short-term political cycles. While many authorities produce 10-year plans for housing or climate action, these can be disrupted by leadership changes or shifting national priorities.

Challenge: Frequent turnover of senior officers and elected members can undermine cultural continuity. Embedding cultural diagnostics and values-based leadership frameworks in organisational development plans can help maintain stability through political transitions.

6. Indulgence (69)

High indulgence reflects a cultural preference for enjoying life and prioritising wellbeing. For councils, this influences HR policies flexible working arrangements, wellbeing programmes, and hybrid models resonate strongly with staff expectations.

Example: Post-COVID, many councils adopted hybrid work models and invested in mental health support, aligning with this cultural trait. These initiatives not only improve employee satisfaction but also enhance retention in a competitive labour market.

Case Study: Cornwall Council Merger

When seven district councils merged into a single unitary authority in Cornwall, the structural change was only part of the challenge. Beneath the surface, cultural differences between the former councils quickly became apparent. While there was strong team spirit and commitment to public service, entrenched practices and local identities resisted harmonisation. Staff were accustomed to their own ways of working, decision-making norms, and informal networks elements that Hofstede’s framework could have predicted. For example:

Power Distance: Some legacy councils operated with more hierarchical decision-making, while others had flatter structures. This created tension when new governance arrangements were introduced.

Individualism vs. Collectivism: High individualism in UK culture meant employees valued autonomy, but the merger required collective behaviours and shared accountability an uncomfortable shift for many.

Uncertainty Avoidance: The low UK score suggests tolerance for ambiguity, yet the merger introduced significant uncertainty, triggering anxiety among staff who feared loss of identity and job security.

The official study recommended moving away from a rigid, top-down approach to an emergent, learning-based model that allowed staff to “unfreeze” from established ways of thinking. This involved:

Creating safe spaces for dialogue to surface concerns and cultural assumptions.

Investing in leadership development focused on adaptive behaviours rather than command-and-control.

Embedding cultural diagnostics into organisational development plans to monitor progress.

Had Hofstede’s dimensions been applied at the outset, leaders could have anticipated these friction points and designed interventions to address them proactively such as aligning communication strategies with low Power Distance norms or introducing team-based incentives to counterbalance individualistic tendencies.

Lesson for Councils: Structural change without cultural alignment is a recipe for resistance. Cultural frameworks like Hofstede’s provide a roadmap for navigating the human side of transformation, ensuring that mergers and partnerships succeed not just on paper but in practice.

Key Takeaways for Local Government Leaders

1. Diagnose before you design

Cultural change initiatives often fail because they start with structural fixes rather than cultural insight. Before launching transformation programmes whether digitalisation, shared services, or mergers councils should use Hofstede’s dimensions alongside internal culture audits to understand the underlying “programming” that drives behaviour. This diagnostic approach helps identify potential friction points, such as resistance to hierarchy or discomfort with uncertainty, and informs strategies that align with staff values.

Practical Action: Combine Hofstede’s framework with tools like staff engagement surveys, focus groups, and organisational values assessments. Use this data to shape communication plans, leadership behaviours, and change management strategies.

2. Avoid stereotypes

National cultural scores provide a useful starting point, but they do not tell the whole story. Councils have their own subcultures shaped by local history, leadership styles, and community expectations. For example, a metropolitan borough may exhibit different cultural traits from a rural district, even though both operate within the UK’s national culture.

Practical Action: Validate assumptions through staff surveys and qualitative feedback. Map cultural differences across departments and service areas to tailor interventions. Avoid “one-size-fits-all” approaches what works for planning teams may not resonate with social care staff.

3. Embed cultural awareness

Culture should not be treated as a side issue; it must be woven into leadership development, partnership agreements, and transformation programmes. Leaders who understand cultural dynamics are better equipped to manage collaboration, resolve conflict, and build trust both internally and with external partners like the NHS, police, and voluntary sector.

Practical Action: Incorporate cultural competence into leadership training and induction programmes. When forming partnerships or shared services, include cultural alignment as a key criterion in governance frameworks. Use Hofstede’s dimensions to anticipate differences and design joint working protocols that respect each organisation’s norms.

Bottom Line: Councils that take culture seriously diagnosing it, validating it, and embedding awareness into every layer of leadership are more likely to succeed in delivering sustainable change and building resilient organisations.

Conclusion

“Culture is more often a source of conflict than of synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance at best and often a disaster.” – Geert Hofstede

This warning resonates deeply in the context of UK local government. Councils operate in a world of complexity balancing statutory duties, political priorities, and partnerships that span sectors and sometimes borders. In this environment, cultural blind spots can derail transformation, fracture collaboration, and erode trust.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions model does not offer a magic solution, but it provides a structured lens to understand the “collective programming” that shapes behaviours within organisations. By diagnosing cultural tendencies before designing change, validating assumptions through staff engagement, and embedding cultural awareness into leadership development and partnership frameworks, councils can turn culture from a hidden risk into a strategic advantage. Ultimately, successful local government leadership is not just about managing budgets or delivering services it is about navigating the human systems that underpin them. Leaders who invest in cultural insight will not only avoid the disasters Hofstede warns of but will create organisations that thrive on collaboration, adaptability, and shared purpose.