Whole-System Thinking: Why Public Service Reform Must Go Beyond Organisational Silos

- truthaboutlocalgov

- Nov 27, 2025

- 6 min read

The Overlap Challenge: Why Silos Hold Back Public Service Reform

One of the greatest challenges in reforming and improving public services is the overlapping nature of different public sector organisations. Adults’ and children’s social care intersect with the NHS and charity partners. Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) provision spans local authorities, health services, and voluntary organisations. Housing development and management often involve partnerships with charities and community groups.

This complexity is not theoretical it is structural. For example, England’s health and care system is now organised into 42 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), each covering populations of 500,000 to 3 million people, bringing together NHS bodies, local authorities, and voluntary sector partners under the Health and Care Act 2022. The aim is collaboration, but as Hugh Alderwick of The Health Foundation notes:

“Partnership policies may not deliver the benefits that many policymakers imagine. Collaboration between local agencies is no replacement for national policy and investment.”

SEND provision illustrates the scale of interdependence. In 2025, 482,640 pupils in England had Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans, an 11% increase from the previous year, while 1.28 million pupils received SEN support without a plan. This means nearly 20% of school-age children require coordinated input from education, health, and social care services. Yet Ofsted and the Care Quality Commission report that the system is “under significant pressure,” with shortages of educational psychologists and fragmented commissioning creating adversarial experiences for families.

Housing partnerships add another layer. Charities and housing associations are critical players: the UK charity sector delivers 69% of homelessness services contracts and 66% of domestic abuse support contracts, and is the largest provider of NHS-commissioned mental health services, supporting 1.5 million people annually. Government spends around £15 billion per year on grants and contracts with charities, split evenly between national and local government.

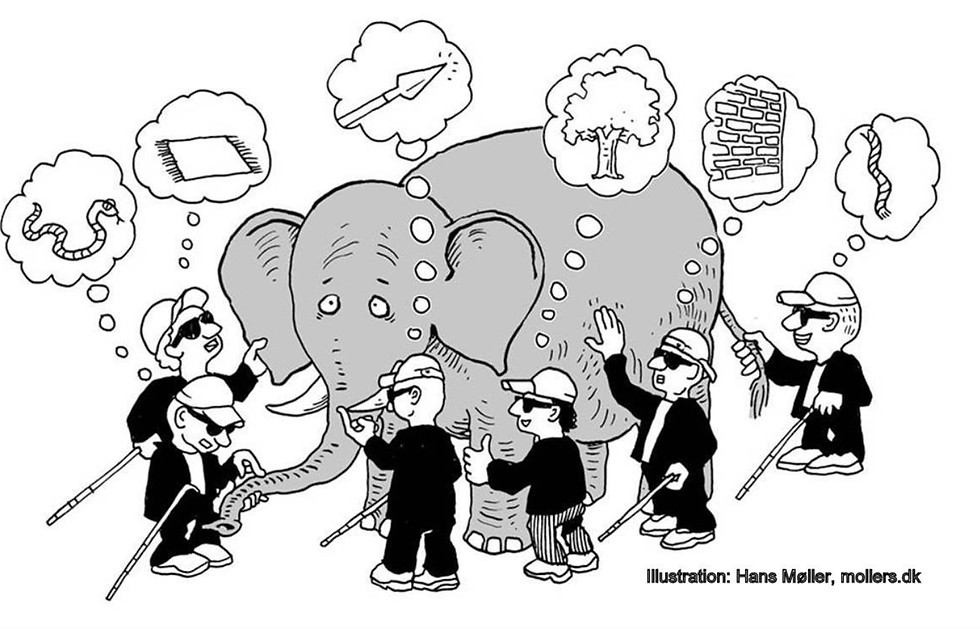

Despite these overlaps, reform discussions often remain confined within organisational boundaries. This is a missed opportunity. As systems theorist Russell Ackoff famously said:

“A system is never the sum of its parts; it’s the product of their interactions.”

True transformation requires us to consider the broader dynamics between institutions and the invisible membrane that connects them. Current siloed structures lead to duplication, inefficiencies, and poor outcomes. The Institute for Government warns that failing to integrate services around citizen needs results in “costly, time-intensive duplication” and risks “reinventing the wheel” at a time when local government capacity is declining.

The Problem with Silos

Local government, the NHS, and other public bodies are structured around outputs they are responsible for delivering. While this makes sense for accountability, it creates barriers to collaboration. Each organisation optimises for its own objectives, often at the expense of system-wide outcomes.

This siloed approach is not just cultural it is systemic. The Institute for Government notes that insufficient collaboration across teams is the main challenge to improving public services, with accountability and funding structures reinforcing departmental isolation. Departments led by separate Secretaries of State and Permanent Secretaries prioritise their own KPIs and budgets, making cross-boundary working “difficult when both management responsibilities and accountability rest with departments”. The consequences are stark:

Duplication and inefficiency – Policies developed in isolation often create unintended consequences, leading to wasted resources and conflicting priorities. For example, fragmented approaches to housing, healthcare, and social care increase costs and diminish outcomes.

Delayed decision-making – Siloed governance slows responses to crises and policy shifts, as approvals and data-sharing require multiple layers of bureaucracy.

Public trust erosion – Citizens experience fragmented services and opaque decision-making, fuelling dissatisfaction. Despite the UK spending £1.2 billion on cloud solutions, manual processes and disconnected systems still dominate many services.

As Rich Corbridge, Chief Digital & Information Officer at DWP Digital, warns:

“Technology is moving at a pace where unless we work together, we won’t be able to operate.”

Labels such as “local government” and “NHS” may now be outdated. They reinforce siloed thinking when what we need is a systems perspective one that recognises interdependencies and designs services around people, not organisational charts. As Alex Fox argues in New Local:

“Without radical reform of the organisations and systems that deliver public services, relational and strengths-based approaches struggle to take hold.”

Capturing the Opportunity for Reform

If we are serious about reform, we must ask:

How do we create the most effective organisational design and development across the whole system?

How do we enable true collaboration between different levels of partnership organisations?

How do we align strategy, technology, and culture across boundaries?

This is not about merging everything into one mega-organisation. It’s about creating connected systems where governance, funding, and accountability mechanisms encourage collaboration rather than competition.

Current funding models often exacerbate fragmentation. Research on local service delivery networks shows that competitive contexts lead organisations to “pursue strategies to promote their own interests rather than working towards a common interest,” including withholding information and projecting success rather than sharing problems.

Breaking these barriers requires:

Integrated governance – Moving from hierarchical control to facilitative leadership that acts as a steward and mediator across organisations.

Shared accountability frameworks – Aligning incentives so that success is measured by system-wide outcomes, not departmental outputs.

Cultural change – Encouraging collaboration through leadership modelling and training, as cultural resistance remains one of the biggest obstacles.

As the Public Finance study concludes:

“Tackling multifaceted issues demands a paradigm shift towards robust cross-government collaboration a strategy vital for fiscal resilience and effective public service delivery.”

The Mid-Flight Challenge

Reform cannot happen in a vacuum. Services must continue to operate while transformation takes place. This means changing strategy, technology, and organisational design mid-flight a daunting but necessary task.

The scale of this challenge is evident in the UK public sector’s digital transformation journey. Despite spending £26 billion annually on digital technology and employing nearly 100,000 digital and data professionals, only 17% of public sector leaders consider their digital transformation completely successful. Almost 47% of central government services and 45% of NHS services still lack a digital pathway, forcing citizens to navigate manual processes and fragmented systems.

Meanwhile, the Infrastructure and Projects Authority reports that the government is managing 227 major projects worth £834 billion, with only 11% rated green for delivery confidence. The majority (72%) are amber, meaning significant risks remain. These projects span critical infrastructure, technology, and service reform yet they must be delivered while frontline services continue to operate under intense pressure.

This is why piecemeal reforms such as Local Government Reorganisation or changes to NHS Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) risk failure. As Lord Ara Darzi warned in his independent review:

“The NHS is in the foothills of digital transformation… IT innovations too often add to, rather than reduce, staff workloads.”

Without a whole-system approach, we will simply rearrange the furniture rather than redesign the house.

Towards Whole-System Thinking

Whole-system thinking is not a buzzword; it is a practical necessity. Public services operate within complex, interconnected systems where changes in one area ripple across others. As Emily Miles, CEO of the Food Standards Agency, puts it:

“Proposed change must take account of reality, rather than landing uselessly into a context that can’t cope with it.”

To achieve meaningful reform, we need:

Shared vision and outcomes across organisations

Current reforms often focus on departmental KPIs rather than citizen outcomes. The Institute for Government warns that this short-termism creates “doom loops” of crisis management rather than long-term improvement.

Integrated governance that balances autonomy with collaboration

Governance models must move beyond hierarchical control to facilitative leadership. Competitive funding environments currently incentivise organisations to “project success rather than share problems,” undermining collaboration.

Data and technology platforms that enable seamless information sharing

Around 30% of central government IT systems are classified as legacy, creating bottlenecks and forcing manual workarounds. True modernisation starts with fixing data foundations and interoperability.

Cultural change to prioritise partnership over protectionism

Change hurts. As Richard Marcinko said:

“People want things to be the same as they’ve always been… But if you’re a leader, you can’t let your people hang on to the past.”

This is the scale of the challenge and the opportunity. If we get it right, we can create public services that are not only efficient but genuinely transformative for the communities they serve.

Call to Action

As leaders, policymakers, and practitioners, we must resist the temptation to focus solely on organisational boundaries. The future of public service reform lies in systems thinking, collaborative design, and courageous leadership willing to embrace complexity.

This is not a theoretical exercise it is a moral and practical imperative. Fragmented services cost billions, frustrate citizens, and exhaust staff. The Institute for Government warns that without integrated approaches,

“government risks repeating cycles of crisis management rather than achieving sustainable improvement.”

Whole-system reform demands boldness:

Leaders who prioritise outcomes over organisational ego.

Policymakers who design funding and governance for collaboration, not competition.

Practitioners who champion innovation while safeguarding frontline delivery.

The question is not whether change is hard it is whether we can afford not to change. Every delay perpetuates inefficiency, inequity, and missed opportunities for communities who deserve better.

The question is: are we ready to take that leap?